Understanding Rappelling: A Comprehensive Guide

Rappelling has long been a fundamental skill for climbers, essential for navigating 5th-class terrain. Traditionally, it was a cornerstone of climbing instruction—new climbers often learned to rappel before scaling their first pitch. However, modern climbing practices have evolved, and rappelling is now less ubiquitous. This shift is due to changes in climbing venues and techniques, but rappelling remains an indispensable skill in many climbing contexts.

In this guide, we aim to educate climbers about the principles, mechanics, and contexts of rappelling while emphasizing safety practices for beginners and seasoned climbers alike.

The Role of Rappelling in Climbing Today

Modern climbing often eliminates the need for rappelling:

- Toprope Venues: Many require no rappelling for setup or cleanup.

- Sport Climbing: Equipped anchors enable quick lowering without rappelling.

- Bouldering: No technical ropework required.

- Climbing Gyms: Most gyms prohibit rappelling entirely.

Consequently, while climbers may understand rappelling conceptually (from belaying experience), fewer have hands-on experience. This gap can lead to misunderstandings about rappelling mechanics, rigging variability, and associated risks. For experienced climbers, complacency can also result in accidents, highlighting the importance of consistent safety practices.

What is Rappelling?

Rappelling, also known as abseiling, is a controlled method of descending steep terrain using a rope. It is commonly used in activities like rock climbing, mountaineering, caving, canyoning, and rescue operations to safely descend cliffs, rock faces, or other vertical surface Rappelling involves lowering oneself down a climbing rope, differing from belaying, where the rope moves while the belayer remains stationary. In rappelling:

- The rope is stationary.

- The climber moves independently, without a belayer.

This independence offers advantages in control and agency but comes with risks. A rappeller must manage their descent without the redundancy provided by a belayer.

How Does Rappelling Work?

Rappelling relies on friction to control the speed of descent. The rope is passed through a belay device, carabiner, or, in some traditional techniques, around the body. The climber or rappeller manages the rope’s tension to control the descent, ensuring it remains smooth and controlled.

Key Elements of Rappelling

Mastering Anchor Systems

Natural vs. Artificial Anchors

Natural anchors utilize existing features like boulders, rock horns, or sturdy trees. Climbers secure these anchors by attaching a sling and carabiner, making use of the environment for support.

In contrast, artificial anchors rely on human-made climbing gear such as camming devices or steel expansion bolts, which are placed directly into the rock for security. While natural anchors are convenient and minimize the need for extra gear, they aren’t always available or reliable in every climbing situation. Artificial anchors, though more versatile, require technical expertise to place correctly.

Selecting the right anchor depends on factors like location, rock quality, and a climber’s skill level. Each type offers unique advantages, making it essential to assess the situation carefully before committing to a setup.

- Anchor System:

The rope must be securely fastened to an anchor point, such as a tree, rock, or artificial bolts. The anchor must be stable and strong enough to support the rappeller’s weight. - Rope:

Dynamic or static ropes are used, depending on the activity. Static ropes are preferred for rappelling due to their minimal stretch. - Friction Device:

A belay or rappel device is used to create friction and allow for controlled descent. Examples include the ATC, figure-8, or Petzl GriGri. - Harness:

A harness provides a secure attachment point for the rope and ensures safety during the descent. - Carabiner:

A locking carabiner connects the rope, harness, and friction device. - Safety Backup:

Techniques like a Prusik knot or a backup belay provide an additional layer of safety.

The Importance of Rappelling in Climbing

Reaching the top of a climb is an achievement, but getting back down safely is just as critical. Most beginners start by lowering on belay, relying on a partner to control their descent. However, rappelling—where the climber self-lowers—is an essential skill for any well-rounded climber.

When Rappelling is Necessary

Rappelling is useful in various situations, including:

- No approach trail to reach the base of your climb (e.g., sea cliffs).

- The need to remove loose rock before climbing.

- Assisting an injured climber when a top-down rescue is required.

- Minimizing wear on rappel rings or anchor systems after cleaning the anchor.

- Cases where walking off, lowering, or downclimbing isn’t an option.

This guide covers the rappel process for a common scenario: descending from a sport-climbing route with two anchor bolts.

Key Considerations

- This guide assumes familiarity with knots, bends, hitches, lead climbing, and lead belaying.

- Since rappelling accounts for a significant number of climbing accidents, learning the proper technique is essential. Always practice under expert supervision before attempting it alone.

- The best way to learn is through mentorship from an experienced climber or by taking a class with a certified instructor.

Checking Your Rappel Gear

Your standard climbing gear doubles as rappel gear, with a few additional essentials.

Personal Anchor System (PAS)

A personal anchor system (PAS) is an important addition for many rappels. It attaches to your harness with a girth hitch through both tie-in points. If you use a different type of tether, some steps may vary.

Backup Autoblock Hitch

You’ll need a 24- to 36-inch length of 5mm or 6mm cord, tied into a loop with a double fisherman’s knot. This is used to create an Autoblock hitch, which serves as a backup for your rappel device. Regularly inspect and replace this cord, as repeated rappels generate friction that can weaken it over time.

Choosing the Right Rappel Device

Not all belay devices are equally suited for rappelling. Always check the manufacturer’s recommendations to ensure your device is approved.

- Tubular belay devices: Most are approved for rappelling and widely used.

- Mechanical belay devices: Typically designed for belaying rather than rappelling.

- Figure-8 devices: Approved for rappelling, with some climbers preferring them over tubular devices.

Optional Gear: Rappel Gloves

Though not essential, many climbers bring rappel gloves, especially for multi-rappel descents, to reduce rope burn and improve grip.

By ensuring you have the right gear and knowledge, you can rappel safely and confidently in a variety of climbing scenarios.

Types of Rappelling Mechanics

- Fixed-Line Rappelling:

- The rope is anchored securely and remains stationary.

- The rappeller descends a single strand of rope.

- Counterweight Rappelling:

- The rope runs freely through a rappel anchor or carabiners.

- The rappeller captures both strands of rope, counterweighting themselves for the descent. The rope can be retrieved from below.

Common Contexts for Rappelling

1. Single-Pitch Rappelling:

- Used when cleaning anchors or in emergencies.

- Local policies or terrain may require rappelling instead of lowering.

2. Multi-Pitch Rappelling:

- Essential for descending multi-pitch climbs.

- Climbers ascend in stages (pitches) and descend in corresponding stages using rappelling.

Safety Considerations and Best Practices

Preparation and Planning

- Research routes through guidebooks, blogs, or local knowledge.

- Carry a topo map and gather detailed information before the climb.

- Inspect equipment before each season and climb. Replace worn ropes, slings, or harnesses as needed.

- Establish clear communication protocols with your climbing team.

Fundamental Principles

- Ensure Security During Setup:

- Use technical security (tethers, slings, personal anchor systems) or non-technical methods (staying seated or away from edges) when near cliffs.

- Use Appropriate Backups:

- Employ backups like prusik knots or autoblocks to safeguard against loss of control.

- Manage Rope Ends:

- Knot rope ends to prevent rappelling off the rope inadvertently.

- Be cautious of unfamiliar terrain, especially in low visibility or fatigue.

- Avoid Entanglements:

- Keep ropes organized and manage rappel devices carefully to prevent entrapment of hair, clothing, or gear.

Appropriate Backups for Rappelling

A rappel backup provides an essential safety mechanism for a rappeller’s brake hand. If the rappeller were to lose grip on the brake strand due to a loss of control, rockfall, or a medical emergency, the backup would hold the rope in place, preventing a fall. There are three common types of backups:

- Friction Hitch Backup

- Firefighter’s Belay

- Assisted Braking Device

Friction Hitch Backup

A Friction Hitch Backup is a versatile option that can be quickly paired with most tube-style rappel devices. However, it requires careful setup to function correctly. Below are key considerations for using a Friction Hitch Backup effectively:

- Proper Configuration: The friction hitch must be tied and dressed correctly to ensure reliable grip on the brake strand. Poorly dressed hitches, iced or frozen knots, or hitches with insufficient friction can fail when needed most.

- Correct Length: The length of the hitch is crucial. If it is too long, the hitch may push against the rappel device, preventing it from gripping the rope. Conversely, a hitch that is too short can prematurely engage, making descent cumbersome.

- Avoid Proximity to the Device: On steep rappels or in situations where the rappeller inverts, the hitch can come dangerously close to the rappel device. This proximity can render the backup ineffective by pushing the hitch along instead of allowing it to engage.

Practical Tips for Using a Friction Hitch Backup

- Practice Setup: Familiarize yourself with tying and dressing common hitches like the Prusik or Autoblock before relying on them in the field.

- Test Engagement: After setting up the hitch, test its ability to grip the brake strand under tension before starting your rappel.

- Inspect Conditions: Ensure the rope and hitch are free of ice, dirt, or other factors that could reduce friction.

- Carry a Backup Plan: If a Friction Hitch Backup proves unreliable, be prepared to use another backup method, such as a Firefighter’s Belay or Assisted Braking Device.The intricacies of rappelling demand careful attention to detail, particularly in the rigging and execution of backups. Whether through precise friction hitch setups, thoughtful extensions, or the vigilant use of safety techniques, ensuring a safe and efficient descent requires a comprehensive approach. Here’s a breakdown of key takeaways for successful rappelling:

- Extensions and Friction Hitch Backups

- Using Extensions: Extending a rappel device away from the harness enhances safety by simplifying the rigging of friction hitch backups. Double-length nylon slings, PAS, or quickdraws with locking carabiners are effective options, with modular extensions offering added utility for multi-pitch scenarios.

- Autoblock Hitch: A popular and versatile choice for backup, the autoblock hitch involves a loop of 5mm nylon that wraps around the brake strands of the rope and secures with a locking carabiner. Proper tying ensures reliability.

- Firefighter’s Belay

- An attentive and properly executed firefighter’s belay can serve as a fail-safe, halting a rappeller’s descent during emergencies. However, like any backup system, its effectiveness hinges on focus, proper positioning, and immediate response.

- Rope Management

- Stopper Knots: Tying bulky knots or conjoining rope ends prevents rappelling off the rope, providing a physical barrier that stops descent.

- Lowering Rope Ends: Managing rope ends by lowering them instead of tossing minimizes risks, avoiding snagging hazards or unpleasant surprises.

- Avoiding Entanglements

- Stay Organized: Ensure ropes are free of tangles and keep hair, clothing, and other items clear of rappel devices.

- Lower, Don’t Toss: Whenever possible, lower ropes gently to maintain control and prevent entanglements or environmental impacts

Body Rappelling?

Body rappelling is a traditional method of descending a rope without using modern equipment like a harness or belay device. Instead, the rope is wrapped around the body to create friction, allowing the climber to control their descent.

Key Features:

- No Equipment Required: Only a rope is needed, making it useful in emergencies or when gear is unavailable.

- Techniques: Common methods include the Dulfersitz rappel, where the rope is passed between the legs, around the torso, and over the shoulder to create friction.

- Challenges: It can cause discomfort, rope burns, or damage to clothing due to the direct contact of the rope with the body.

Applications:

Body rappelling is primarily used in emergency situations or by climbers and mountaineers who have learned traditional techniques. Modern gear has largely replaced this method for regular use due to its safety and comfort advantages.

Traditional Body Rappelling Techniques: Stomach Rappel, Shoulder Rappel, and American Side Rappel

Body rappelling involves using your body as the primary friction point for controlled descent down a rope. These methods were widely practiced in the past when modern equipment was not available. While effective in certain scenarios, these techniques have significant risks and should only be attempted with proper training and under the guidance of a professional.

1. Stomach Rappel

- Description: In this method, the rope is passed around the waist or stomach area to create friction, allowing for descent. The climber uses their hands to control the rope and regulate speed.

- Advantages: Quick to set up and doesn’t require complex positioning of the rope.

- Disadvantages: Extremely uncomfortable, as the rope digs into the stomach, causing friction burns or bruising. It also offers limited control compared to other methods.

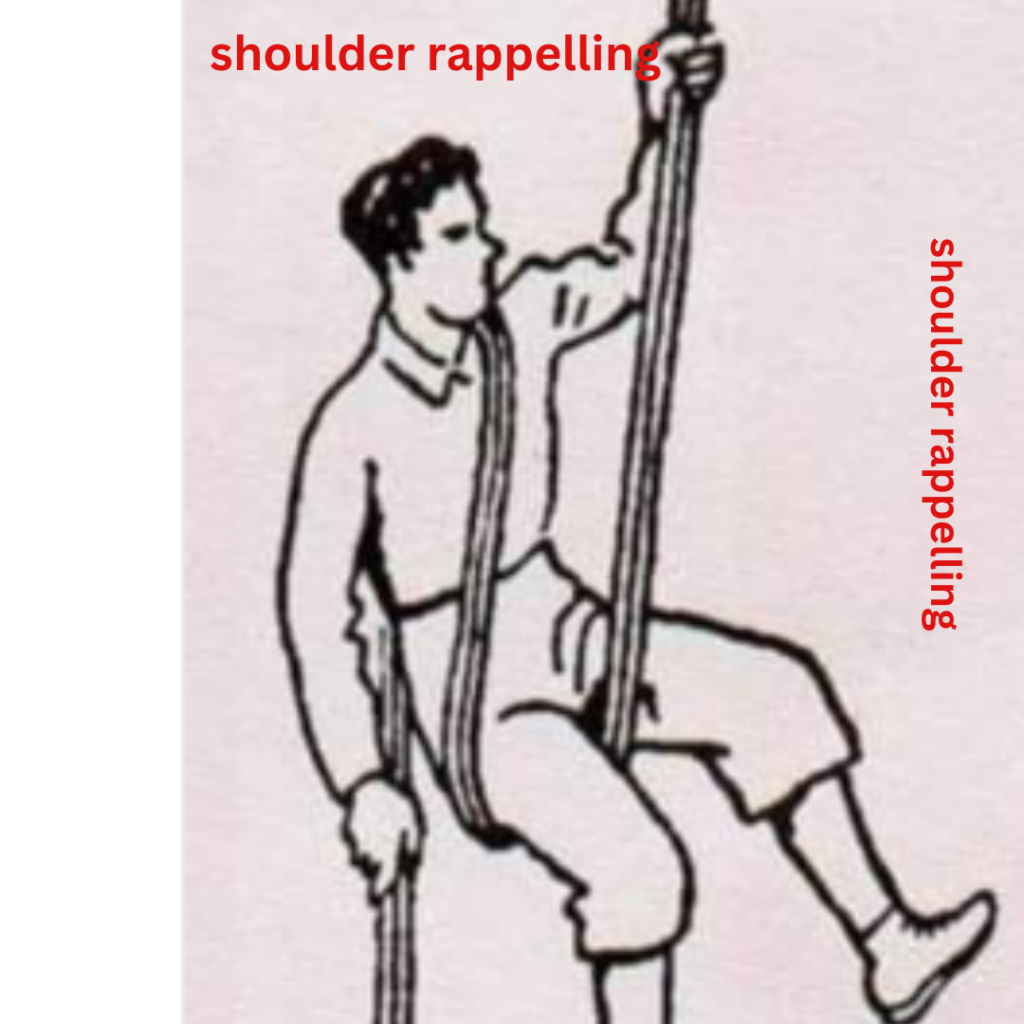

2. Shoulder Rappel

- Description: The rope is passed over one shoulder, across the back, and under the opposite arm, forming a diagonal line. The climber uses one hand to guide the rope above and the other to control the brake below.

- Advantages: Easier to control than the stomach rappel because the rope is distributed more evenly across the body.

- Disadvantages: Causes rope burns on the shoulder and under the arm, especially with prolonged use. It requires proper positioning to prevent losing control.

3. American Side Rappel

- Description: Similar to the shoulder rappel but with adjustments to make it more comfortable. The rope is passed diagonally across the body, focusing on friction control at the side of the body.

- Advantages: More intuitive and ergonomic compared to the shoulder rappel, with better weight distribution.

- Disadvantages: Still poses risks of rope burns and discomfort, especially with improper technique or clothing.

Other Traditional Body Rappelling Techniques

- Cross Rappel: Combines elements of the Dülfer and shoulder rappels to create a crisscross pattern across the chest.

- Thigh Rappel: Focuses friction on the legs and thighs, often used for shorter descents.

- Hand-Over-Hand Descent: Involves lowering oneself without using friction points, making it extremely dangerous and not recommended.

Safety Steps for Body Rappelling

- Anchor Stability: Ensure the rope is securely attached to a strong, stable anchor that can bear your weight.

- Clothing: Wear durable, heat-resistant clothing like Gore-Tex or thick pants to minimize friction burns.

- Practice in a Controlled Environment: Before attempting any body rappel, practice under the supervision of a well-trained instructor in a safe location.

- Use a Backup: Incorporate a safety knot like a Prusik hitch as a backup in case of a slip.

- Avoid Long Descents: These methods are best for short descents due to the physical strain and increased risks involved.

- Never Rush: Descend slowly to maintain control and prevent overheating the rope or damaging clothing.

- Inspect the Rope: Ensure the rope is free of damage, knots, or wear before use.

Why You Shouldn’t Attempt These Without Guidance

Body rappelling techniques, while innovative, are inherently risky. They lack the safety and comfort of modern harnesses and belay devices, and improper execution can result in severe injuries. Always learn these methods from a certified mountaineering or climbing instructor and use them only in emergencies or controlled environments.

Remember, modern equipment exists for a reason, and traditional methods are often a last resort. Prioritize safety, and never compromise on training or preparation.

Final Thoughts

Rappelling, while not as commonly practiced as before, remains a vital skill for climbers in many scenarios. Understanding its mechanics, contexts, and safety principles can prevent accidents and improve efficiency. Whether you’re a novice climber learning the basics or an experienced adventurer revisiting best practices, a mindful approach to rappelling ensures safety and success on every descent.